By Elliott Lelaure, UNH History Program Graduate Student

Located near Tamworth at the eastern end of the Wobanadenok’s (White Mountains) Sandwich range, Mount Chocorua is widely known among Granite Staters for its dramatic profile and picturesque hiking trails. It is perhaps more famous still for its early eighteenth century colonial folklore – specifically, the various legends and curses associated with the Pigwacket (Pequawket) Chief after which the mountain takes its current name.

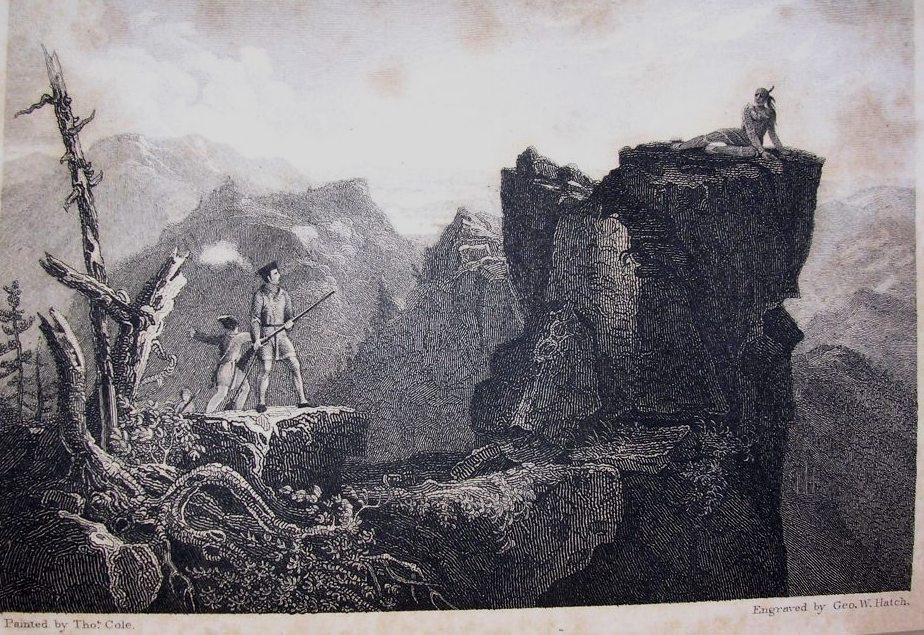

Each version tells the story of Chief Chocorua’s death at the mountain summit, but they vary wildly in their descriptions of the relevant context and circumstances. The most common version, as remembered by locals and still reprinted across tourist brochures and Wikipedia pages, is derived largely from the 1829 account of Lydia Maria Child – a Boston-based writer who first wrote the legend as an accompaniment to a printed engraving of the same scene by celebrated landscape artist Thomas Cole. In Child’s story, Chocorua’s pre-teen son died around 1720 after accidentally ingesting fox poison during a brief stay with the Anglo-American Campbell family of Tamworth. Soon thereafter, Cornelius Campbell discovered the murder of his wife and children and quickly attributed blame to the grieving Chief. In an act of revenge, settlers pursued Chocorua to the top of the nearby mountain where he was either shot by Campbell or – accounts differ on this point – he leapt to his death on the rocks below. His final words, Child tells us, served to place a curse on his killers:

“Lightning blast your crops! Wind and fire destroy your dwellings! The Evil Spirit breathe death upon your cattle! Your graves lie in the war-path of the Indian! […] Chocorua goes to the Great Spirit – his curse stays with the white men!”

With apparent success, the curse took hold and the local settlers struggled for decades to come with poor harvests and diseased livestock – only through later scientific research could these facts be attributed to the area’s mineral-contaminated soil rather than any Indigenous curse. Alternative versions of the legend make no mention of a curse at all. One claims that Chocorua fell to his accidental death while hunting; another suggests that the Chief voluntarily exiled himself to the mountain as part of a neutrality pledge to the everencroaching English and only later committed suicide when conflict eventually broke out between the settlers and his fellow Pequawkets. According to anthropologist and archaeologist Mary Ellen Lepionka, these contrasting accounts of Chocorua’s death cast doubt on their basis in historical fact. Those involving the Chief’s suicide are particularly unlikely given Lepionka’s observations that “suicide was not the Algonquian way” and an Abenaki warrior would “more likely have sacrificed himself in a violent confrontation and gone down fighting.”

There is even reason to doubt the existence of Chief Chocorua himself – his name is not recorded either in Abenaki oral tradition or early colonial primary sources. Instead, Lepionka suggests he may have been a “composite persona” invented by early settlers to dramatize and represent the local Abenaki population as a whole. If true, Chocorua’s legacy as a fictional menace to settler wellbeing and agricultural fortune is a powerful indication of their broader mistrust and persecution of the land’s original inhabitants. Furthermore, Lepionka argues that his very designation as “Chief” represents a European construct imposed on the Abenaki who, in this period at least, were instead organized as “patrilineal bands, led by sagamores” and elected Sachems.

Older research from historian Lawrence Shaw Mayo also supports that the story is more likely a product of colonial fiction than Abenaki history. Any factual basis for the legend of Chocorua, Mayo argues, was lost when Child “embroidered it to her heart’s content” when first writing the legend in 1829. Indeed, Child’s writing is rife with colonial stereotypes and hateful characterizations of Indigenous historical actors (whether real or not) – the Chief, she states, had a “mind which education […] would have nerved with giant strength, but, growing up in savage freedom, […] wasted itself in dark, fierce, ungovernable passions.” Clearly, Child’s perspective was well-aligned with those many colonial and settler voices who sought – and in many cases continue – to contain examples of Indigenous resistance within narratives aimed at rationalizing their attempted eradication and replacement.

If there is any historical evidence for the legend of Chocorua’s curse, its origins may be even more sinister than colonial accounts have claimed. In her analysis, Lepionka notes that settlers of the Massachusetts Bay colony could petition their governor for scalp commissions worth up to three hundred British pounds – in this way, they were “encouraged to commit genocide” and provided with a way to enrich themselves at the expense of Indigenous lives and communities. Accordingly, she suggests that one mid-nineteenth century version of the legend where an Abenaki warrior was trapped at Chocorua lake and then killed by white bounty hunters is, ultimately, the “most plausible” of these different narratives.

To counter the colonial prejudices that permeate conventional accounts of Chocorua’s curse, it is vital that we consider an Abenaki basis for the mountain’s current name. While Lepionka concedes that its original name is likely lost to history (certainly, it would have vastly predated European contact and eighteenth-century folklore) she offers a linguistic

analysis by which Chocorua may first have referred to the mountain and, only through erroneous colonial interpretation, later applied to the Pigwacket leader and his supposed curse. Choc, she notes, may be derived from an Eastern Algonquian word for eroded rocks – today, it is also found in Quebec’s Chic-Choc mountain range and in the name Agiocochook – the Abenaki appellation of New Hampshire’s Mount Washington. Corua, she continues, is a pre-contact term for serpent – especially one associated with water or mountain springs. In combination, Lepionka concludes that Chocorua may plausibly signify the “Home of the Water Serpent” and, through colonial mistranslation and linguistic corruption, was later applied to local figures and legends.

Despite the lack of clarity over the naming of Mount Chocorua and its associated folklore, its known history is a damning indictment of the extent to which anti-Indigenous colonial attitudes have imprinted themselves upon our collective cultural memory and, indeed, upon our landscape itself. Even when New Hampshire’s mountains are named for

Indigenous leaders and not for presidents, it is often done from a colonial perspective to service a colonizing narrative where Indigenous resistance is framed – with little regard for historical fact – as a threat to the civilization and cultivation of the American frontier. It is beyond time that this narrative is challenged – and through truthful investigation of the historical record – corrected. In this way, it is not only possible but necessary to recognize Indigenous communities both past and present as the original stewards and protectors of this land.

Bibliography

Child, Lydia Maria. “Chocorua’s Curse.” The Token: A Christmas and New Year’s

Present, edited by Samuel Griswold Goodrich, 257-265. Boston, MA: Carter and Hendee,

1829.

Mayo, Lawrence Shaw. “The History of the Legend of Chocorua.” The New England

Quarterly, Vol. 19, No. 3 (September 1946): 302-314.

Lepionka, Mary Ellen. “Chocorua Redux: Revisionist History of a Name.” Chocorua Lake

Conservancy. March 1, 2019.