By Paul King, Tamworth resident and owner of Paul King Surveying

Abstract

In Ossipee, NH, there is an earthen mound known as the Indian Mound. It is 2.5 meters (m) high and has a base diameter varying from 25 to 30m, on a generally flat site. Adjacent to the Indian Mound was a village of the Abenaki tribe. There was also a large fort constructed by the Abenaki. In 1676, the fort was burned by the English. In 1959, the 0.6-acre fort site was conveyed to the Ossipee Historical Society. The outline of the fort was still visible in 1962. In 1965, the fort site was bulldozed and made part of the Indian Mound Golf Course second green. Two boundary surveys show the fort site parcel, owned by the Ossipee Historical Society. The azimuth (a horizontal clockwise angle from true north) and distance from the Indian Mound to the fort site are 57.5 degrees and 350m. The summer solstice sunrise at the Indian Mound is 57.5 degrees. Thus, the Abenaki fort was constructed on the summer solstice sunrise alignment from the Indian Mound.

Introduction

Archaeoastronomy is the study of ancient astronomic observatories. Many archaeoastronomical sites are found worldwide and in the United States (Williamson, 1984). In the western third of the United States, archaeoastronomical sites generally consist of stone structures. Examples are the Bighorn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming (Eddy, 1974) and Chaco Culture National Historical Park in New Mexico (Frazier, 2005).

Mississippi and Ohio River drainage areas (Squier and Davis, 1848/1973). Examples of earthen mounds are Ozier Mound at the Pinson Mounds State Archaeological Park in Tennessee (Milner, 2021), Etowah in Georgia (Toner, 2008), and the best known, Cahokia in Illinois (Iseminger, 2010). As far as we presently know, the Northeast has very few Native American earthen mounds.

Some earthen mound sites also have archaeoastronomic elements. Examples of earthen mounds sites that also have archaeoastronomical elements include the Woodhenge at Cahokia in Illinois (Iseminger, 2010), another utilized raised large alignment poles at Sunwatch Indian Village in Ohio (Lepper, 2005), a lunar observatory at the Newark Earthworks in Ohio (Hively and Horn, 2013), and the amazing Serpent Mound in Ohio (Hardman and Hardman, 1987).

The Northeast has only a few proposed Native American archaeoastronomical sites. A commercial tourist site, America’s Stonehenge, in Salem, NH, purports to be archaeoastronomical. Unfortunately, the site owners in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries set and rearranged many of the stones. The compromised integrity of the site makes it impossible to verify its authenticity. (Starbuck, 2006). The Northeast does have many stone chambers. Marine biologist Barry Fell and others claim that these were made by European Neolithic or Bronze Age settlers (Neudorfer, 1980) and that two have astronomical alignments: the Gungywamp Calendar Chamber in eastern Connecticut (Olsen) and Calendar II in Vermont (Legends of America). However, an extensive study in Vermont concluded that the stone chambers were nineteenth-century root cellars or other farm structures (Neudorfer, 1980).

Ossipee Indian Mound

Ossipee, NH, is home to a mound known as the Indian Mound. It is in the middle of the original nine holes of the Indian Mound Golf Course, formerly the Indian Mound Farm. The Mound is slightly oval-shaped. The long axis is about 30m, azimuth 330 degrees. The short axis is about 25m. The height is about 2.5m. The location is N43.775970, W71.158720.

From the late 1700s until 1950, locals believed it was a Native American burial mound, with speculative claims that 8-10,000 bodies were buried in the mound (Cook, 1989). The newly formed NH Archaeological Society organized a dig into the Indian Mound as their first project. No formal report was prepared. In a 1950 press release, they stated that they found no artifacts and concluded the mound was a glacial deposit (Brown, 1950). The dig was described with additional details, again by the NH Archeological Society:

The first real step taken was to prove, by careful digging, that the famous Ossipee Indian Mound is merely a kame, deposited by a retreating glacier. Although there may have been an intrusive burial in the mound, the mound itself could not have been thrown up by Indians. Prof. Meyer of the University of New Hampshire carefully examined the mound, which had been cut by trenches both lengthwise and across. The lowest stratum showed blue clay, followed in turn by yellow sand, then by white sand, with six inches of loam on the surface. Except for the very top, these strata showed no sign of being disturbed (Crosbie, c1953).

No known investigation has been made by a surficial geologist to confirm it is a kame, a different surficial geology feature, or possibly made by Native Americans. Surficial geology mapping of the Ossipee Lake quadrangle took place during 2022-2023 by a combined effort of the NH Geological Society and the US Geological Survey. Unfortunately, the Indian Mound was not investigated. The observation of blue clay is surprising. Few clay deposits exist in the Ossipee, NH area (USDA, 1977). Two auger holes in the golf fairways, adjacent to the Indian Mound, contained only loam and no clay.

The Ossipee, NH area is the ancestral home of the Abenaki community called Ossipee; historical accounts suggest a substantial village community in the vicinity of the Indian Mound.

Two tomahawks and many pieces of coarse earthen ware have been found in the surrounding meadow; and on the northern side of the river, when the land was first cleared, the hills where corn grew, were distinctly visible. From these facts, the inference is irresistible that this was once the residence of a formidable tribe of aborigines of the country (Boutin, 1861).

Without solid archaeological evidence, the Indian population can only be guessed (Cook, 1989). The estimated village size was 400-500 inhabitants in the pre-epidemic period before 1616 (Cook, 1976). Boutin estimates the Ossipee community at 1,000 individuals in 1623 (Boutin, 1861).

Most of the land around Ossipee Lake and the subsequent bays is either outwash sand/gravel deposits or wetlands with no agricultural value. The area adjacent to the Indian Mound, at the present golf course, is visually flat and contains loamy soils. These soils are suitable for agriculture, but given the location, are at risk of flooding (USDA, 1977). Near the Indian Mound is the site of an Abenaki Fort. Based upon the evidence of agricultural soils and the Abenaki Fort, it seems likely that the Abenaki village was located around or adjacent to the Indian Mound. Now the site has raised golf tees and greens. Before the golf course construction, the site was visually flat, and the Indian Mound would have been the only prominent feature.

Abenaki Fort

The Indian Mound is 650m west of Ossipee Lake. Ossipee Lake was an important trading and transportation center for Indigenous peoples (Cook, 1989). Trade was important because of the Hornfels mine on the north side of the Ossipee Mountains (Ives and Leveillee, 2005). Hornfels was used for projectile points and other stone tools.

From Ossipee Lake, the Ossipee and Saco rivers flowed downstream to the Atlantic Ocean at Saco, ME. The Pine River and minimal portaging provided access south to the Salmon Falls and Piscataqua Rivers. The West Branch River, Silver Lake, and minimal portaging provided access north to Conway, NH, and Fryeburg, ME, the location of another Abenaki community known as Pequawket. The Bearcamp River and minimal portaging provided access west to Squam Lake and Winnipesaukee Lake. Both lakes flow to the Merrimack River. Unfortunately, these rivers also provided access for attack from adversaries.

There were two forts constructed in this area. There was a large, solidly built fort of the Abenakis in the 1600s, and a small “fort” was quickly put together for temporary shelter by Capt. John Lovewell.

Below is an early description of the Abenaki Fort:

The Indians belonging to those Parts had not many Years before hired some English Trades to build them a Fort their Security against the Mohawks, which was built very strong for that Purpose fourteen foot high with Flankers at each Corner (Hubbard, 1677/1865/1969).

In 1676, 130 English militiamen and forty Indians marched up the coast to Ossipee. They found the area deserted and burned the Abenaki Fort to the ground (Hubbard, 1677/1865/1969).

In the Spring of 1725, Capt. John Lovewell and 46 other men from the Merrimack Valley towns of Massachusetts set off on a third march against the Abenaki. On the way north, one man fell sick in Ossipee.

Then they Travell’d as far as Ossipy, and there one Benjamin Kidder of Nurfield falling Sick; the Capt. Made a Halt, and tarried while they built a small Fortification, for a place of Refuge to repair too, if there should be Occasion. Here he left his Doctor, Serjent and Seven other men, to take care of Kidder (Symmes, 1725).

Another description from a year later similarly refers to the Lovewell Fort as a small fort near Ossipee (Penhallow, 1726/1859). Note, neither Symmes nor Penhallow describes the location of Lovewell’s Fort as anything more than Ossipee. They make no mention of Lovewell’s Fort being at the location of the Abenaki Fort.

Lovewell’s small fort was constructed quickly. Lovewell and the other men continued north. A great battle ensued at what is now Fryeburg, Maine. Benjamin Hassell fled the battle and returned to the fort. Immediately, he and ten men abandoned the fort and fled back to Massachusetts (Cray, 2014). Obviously, the men did not have any confidence in the ability of the Lovewell Fort to provide any serious protection.

Belknap in 1812 described what was presumed to be Lovewell’s Fort as “a stockade fort on the west side of Great Ossapy Pond” (Belknap, 1812).

Farmer and Moore wrote a detailed description in 1823 of what they presumed was Lovewell’s Fort:

About halfway between the mound and the western shore of the lake are the remains of a fort built by the brave Capt. Lovewell. … This fort, which was built almost a century ago, appears to have been only palisaded, or a stockade fort. Its eastern face fronted the lake, and was situated on the top of a small bank, which ran along from the river before mentioned to the southward. At the north and south ends of the fort, considerable excavations of earth were made resembling cellars in size and appearance. The ditch, in which the palisades were set, can be traced round the whole tract which the fort contained, which appears have been about an acre. The excavation at the north end of the fort is much the largest. This almost reaches the river; and here the water for its supply was probably obtained (Farmer and Moore, 1823).

These authors attribute the fort to Capt. Lovewell, but based upon the description of the size and extensive excavations, this is clearly the Abenaki fort site from the 1600s.

Boutin, in 1861, restates the Symmes’ 1725 description of Lovewell’s Fort and also includes Farmer and Moore’s 1823 description as a footnote (Boutin, 1861). In 1865, Kidder did the same as Boutin (Kidder, 1865). Parkman, in 1898, describes Lovewell’s Fort as “a small fort or palisaded log cabin” (Parkman, 1898). Sylvester, in 1910, describes Lovewell’s Fort as a “small fort,” and, as with Boutin and Kidder, also includes Farmer and Moore’s 1823 description as a footnote.

The Federal Writers’ Project described the fort site in 1938:

The Site of an Early Fort, built here by English troops… It is known that as early as 1650 and 1660 English workmen were sent here to assist the Ossipee Indians against the Mohawk. A timber fort 14’ high was constructed and used by the Indians, until they reversed their loyalty and turned against the white men. In 1676 the fort was destroyed by English troops, but the site was occupied later by Massachusetts and New Hampshire soldiers. In 1725 Captain Lovewell built a stockade here as a base for Indian attacks that culminated at Lovewell’s fight in the neighborhood of Conway (Writers, of the Federal Writers’ Project, 1938).

The Federal Writers’ Project authors had obviously read Hubbard’s 1677 descriptions and correctly identified the fort site as the Abenaki Fort. They further note that the fort site is also where Lovewell built his smaller fort. There is no source for why the authors felt this was where Lovewell built his smaller fort.

A 1962 description of the Abenaki Fort:

A short walk from the Mound, toward the lake and near the forest border of the field, brings one to a level spot where one may trace indistinctly in the turf outlines of a large rectangular enclosure. Near its western boundary there sparkled a large clear spring (Poor, 1962).

Poor also quotes Dr. William Teg (historian of Porter, Hiram, and Brownfield, Maine) about the Abenaki fort:

It was rebuilt by Captain Lovewell’s Rangers in 1725 just before their march on Pequawket (Poor, 1962).

Cook restates Hubbard’s 1677 description of the Abenaki Fort and then locates the Lovewell Fort at the Abenaki Fort site without any source for this conclusion.

At Ossipee Lake, one of the men fell sick, and Lovewell hastily built a shelter to house him and some of the expedition’s supplies. (This shelter occupied a part of the site of the old Indian fort and has often been confused with the earlier structure.) (Cook, 1989)

Schultz and Tougias restate Hubbard’s 1677 description of the Abenaki fort and its destruction and then note the location:

Today, where the fort once stood, is the second tee of the Indian Mound Golf Course in Ossipee. It is the property of the Ossipee Historical Society (Schultz and Tougias, 1999).

Note: It is actually the second green, not the second tee.

Cray, in 2014, notes Lovewell stopped at Ossipee because Kidder was ill and constructed a stockade. Cray describes the stockade in terms similar to the Abenaki Fort:

The fort’s outline still visible many years later, showed that considerable quantities of earth had been remove in digging cellars. Its location adjoined a river providing a ready source of water (Cray, 2014).

All this leaves us with descriptions of the Abenaki Fort as large, palisaded, well-built, and having a water supply from extensive excavations. Its location is between the Mound and the Lake. Historians Farmer and Moore, Boutin, Kidder, Sylvester, and Cray incorrectly refer to this site as the Lovewell Fort. Presumably, these historians were unaware of the existence of an earlier Abenaki Fort.

The Federal Writers’ Project, Teg, and Cook state that Lovewell’s small fort was constructed at the site of the larger Abenaki Fort. No source for Lovewell’s Fort being located at the Abenaki Fort site was found. Lovewell’s Fort might have been at the Abenaki Fort site, but it could have been anywhere in the general Ossipee area. Lovewell’s Fort was constructed 49 years after the Abenaki Fort was burned and the area abandoned. The area would have grown back into dense, small-diameter trees. This forest type would not have been optimal for constructing or defending a fort. Logically, the Lovewell Fort would have been some other location in the general Ossipee area. The site of the Lovewell Fort is not important to this research, but it is important not to confuse it with the Abenaki Fort.

The site of the Abenaki Fort was conveyed from Robert C. Draper, the owner of the Indian Mound Farm, to the Ossipee Historical Society in August 1959 (CCRD, Book 338, Page 425). The description in the deed was somewhat crude but adequate enough to know the location. In 1965, the Historical Society permitted the Fort site to be used as part of the new golf course (CCRD Book 388, Page 509). The site was bulldozed and now contains most of the second green and a golf cart path. In 1976, Stephen Boomer, an Ossipee surveyor, surveyed the 0.6-acre site of the Abenaki Fort with compass and tape techniques (CCRD Book 633, Page 6). A modern, professional survey of the 0.6-acre site was done by White Mountain Survey Co., Inc. of Ossipee, NH. Both surveys incorrectly labeled the site as Capt. Lovewell’s Fort.

Even though the site was bulldozed, we are fortunate to know the location. The center of this 0.6-acre site is N43.777670, W71.155040. The azimuth from the Indian Mound is 57.5 degrees; the distance is 350m.

Native Americans set and utilized forest fires for many purposes (Williams, 2005). One purpose was defense. Since the Abenaki had a fort for defense, it is a reasonable presumption that they also burned the forest from the area of the mound and fort to the Lake for defense. This would enable the Abenaki to see the approach of any attack from adversaries. The burnt forest also provided better hunting and foraging.

Summer Solstice Sunrise

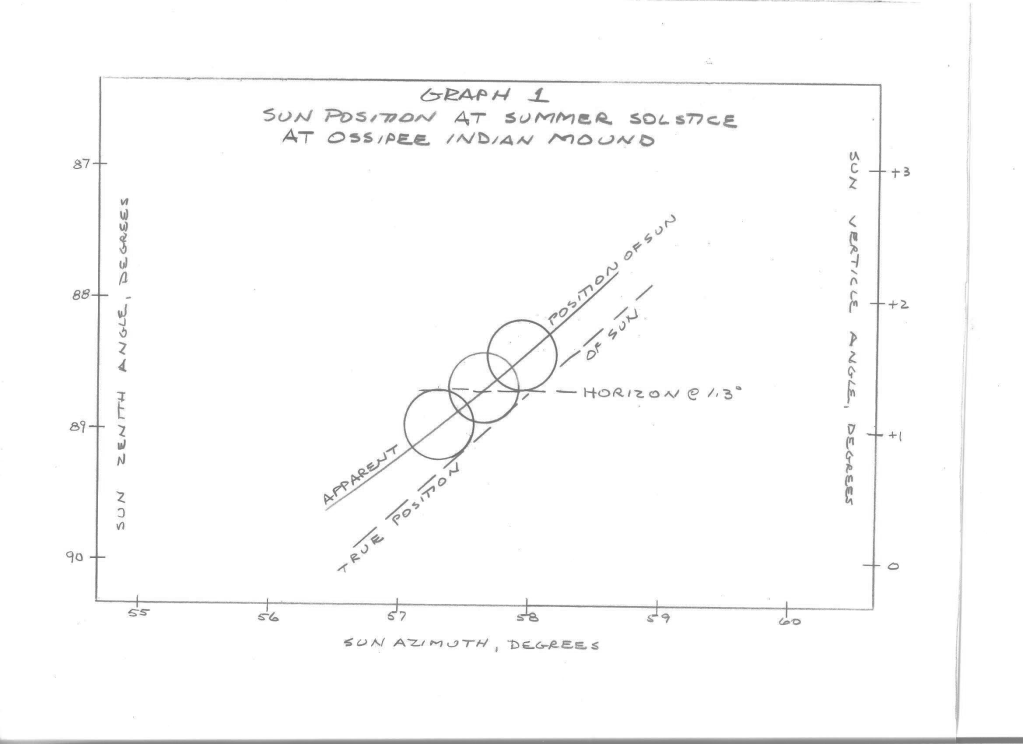

At the latitude of the Indian Mound, at the Summer Solstice sunrise, the sun’s center true position is at an azimuth of 56.57 degrees (USNA MICA, 1998-2005). The apparent sunrise is earlier at 55.9 degrees because of atmospheric refraction. The formula used for refraction’s effect is one Bennett developed (Bennett, 1982). The result of refraction calculated by Bennett’s formula was a very slight decrease to an assumed temperature of 20 °C. The calculated effect of refraction is approximate because it depends on the temperature, pressure, and humidity.

The horizon at an azimuth between 57 and 58 degrees, ignoring trees between the Indian Mound and Ossipee Lake, is at a ridge at 10.25 km. The ridge ground elevation is 1120 ft. Assuming tree heights of 80 feet, the highest top of tree elevation is 1200 ft (366m). The vertical angle of this horizon, including a slight decrease for curvature of the Earth, is +1.3 degrees (NGS Toolkit, 2018).

The sun’s true position and apparent positions are shown in Graph No. 1. The upper limb of the sun’s apparent position is at the horizon at an azimuth of 57.2 degrees. The center of the sun’s apparent position is at the horizon at an azimuth of 57.6 degrees. The lower limb of the sun’s apparent position is at the horizon at an azimuth of 57.9 degrees. This summer solstice sunrise from the Indian Mound is directly over the location of the Abenaki Fort site.

The Pleiades

The cluster of stars known as the Pleiades or the Seven Sisters was and is a significant cluster of stars to the Abenaki (Besaw, 2021). The 2000 (ep J2000) coordinates of the Pleiades are Right Ascension 3h 46m 24s and Declination 240 06’ 50” (simbad.u-strasbg.fr). These coordinates change slightly as one goes back in time because of precession. The equations for these changes per year are (Tatum, 2020):

Change declination = 19.9” cos right ascension

Change right ascension = 3.07s+1.33s (sin right ascension)(tan declination)

The equation for the azimuth of the Pleiades at rising, where the elevation is zero, is:

Azimuth = arc cos (sin declination/cos latitude) (Brinker and Minnick, 1987)

The resulting coordinates and azimuth of the Pleiades, at rise for previous centuries, are:

| Year | Change Right Ascension | Right Ascension | Change Declination | Declination | Azimuth at Rising |

| 2000 | 3h 46m | 55.5° | |||

| 1900 | 06m | 3h 40m | 18′ | 23° 49′ | 56.0° |

| 1800 | 06m | 3h 34m | 19′ | 23° 30′ | 56.5° |

| 1700 | 06m | 3h 28m | 20′ | 23° 10′ | 57.0° |

| 1600 | 06m | 3h 22m | 20′ | 22° 50′ | 57.5° |

The azimuths shown are the true position of the Pleiades. The same adjustments for refraction and vertical angle to the horizon made for the sunrise can be made to the Pleiades. In 1800, the Pleiades rose in the same location as the summer solstice sunrise. During the 1600s, the Pleiades rose within a degree of the summer solstice sunrise and the azimuth from the Indian Mound to the Abenaki Fort. This is quite close, given that the Pleiades is a cluster of stars, not a single point.

Also, the Pleiades are dim, with only magnitude 4. Because of extinction, the atmosphere’s absorption and scattering of light, the Pleiades constellation is not visible until its altitude is at least 4 degrees (Magli, 2020). Thus, an observer of the Pleiades, after it is visible, would need to watch its trajectory and approximate back to the point on the horizon where it actually rose. Since this is an observer’s approximation, this is close enough to presume the fort was built on the azimuth from the Indian Mound to the approximate rise of the Pleiades.

Conclusion

The Abenaki constructed their fort on the azimuth from the Indian Mound to the summer solstice sunrise and close to the azimuth of the rise of the Pleiades. An alignment to the summer solstice sunrise is typical for archaeoastronomic sites around the world. This is significant because of the lack of other accepted archaeoastronomic sites in the Northeast.

One can envision the Abenaki, at the community called Ossipee, sitting on the Indian Mound, overlooking their fields of maize, cucurbits, and beans, on the summer solstice morning, watching the sun rise directly over their fort.

This paper also counters the local belief that the Abenaki Ossipee Lake fort site was constructed by Capt. Lovewell.

References

Belknap, Jeremy, 1812. The History of New Hampshire, Vol. 2. Remich and Mann, Dover, NH, page 53.

Bennett, G.G. 1982. “The Calculation of Astronomical Refraction in Marine Navigation.” Journal of Navigation, vol. 35, no 2: 255-259, Equation G.

Besaw, Rhonda. 2021. (Abenaki Nation of NH), personal correspondence.

Bouton, Nathaniel P, 1861. Capt. John Lovewell’s Great Fight with the Indians at Pequawket, May 8, 1925, by Rev. Thomas Symmes, A New Edition With Notes by Nathaniel Bouton. P. B. Cogswell, Printer, Concord, NH, pages 18-19.

Brinker and Minnick, editors, 1987. The Surveying Handbook. Van Nostrand Reinhold Co Inc, New York, NY, Chapter 15 by Eglin, Richard L., Knowles, David R., and Senne, Joseph H., Equation 15-12.

Brown, Percy S. 1950. “The Work and Aims of the New Hampshire Archaeological Society.” Copy filed at NH Historical Society, 571.6, N532A.

CCRD, Carroll County Registry of Deeds, Ossipee, NH.

Cook, Edward M., Jr. 1989. Ossipee, New Hampshire, 1785-1985: A History. Peter E. Randall, Publisher, Portsmouth, NH, pages 3-16.

Cook, Sherburne F.. 1976. The Indian Population of New England in the Seventeenth Century. University of California Press.

Cray, Robert E., 2014. Lovewell’s Fight, War Death, and Memory in Borderland New England. University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst and Boston, page 20.

Crosbie, Laurence M. Undated c1953. “Notes on the Society.” The New Hampshire Archeologist, Vol. 4, No. 1. (Available at UNH Library.)

Eddy, John A. 1974. “Astronomical Alignment of the Big Horn Medicine Wheel.” Science, vol. 184, issue 1414: 1035-1043.

Farmer and Moore, 1823. “Indian Mound in Ossipee”, Collections, Historical and Miscellaneous and Monthly Literary Journal, Vol II. J. B. Moore, Concord, pages 45-46.

Frazier, Kendrick. 2005. People of Chaco. W.W. Norton and Co., New York, NY, chapter 10.

Hardman, Clark and Marjorie. 1987. “The Great Serpent and the Sun”, Ohio Archaeologist, Vol. 37, No. 3: 34-40.

Hively, Ray and Horn, Robert, 2013. “A New and Extended Case for Lunar (and Solar) Astronomy at the Newark Earthworks,” Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 38, No. 1.

Hubbard, William. 1677/1865/1969. History of the Indian Wars in New England from the First Settlement to the Termination of the War with King Philip. Kraus Reprint Co, New York, NY, pages 179-187.

Iseminger, William R. 2010. Cahokia Mounds: America’s First City. The History Press. Charleston, SC, pages 121-136.

Ives, Timothy H. and Leveillee, Alan. 2005. “Busy in the Shadow of the Ossippee Mountains: Archaic Hornfels Workshops and a Paleoindian Site in Tamworth, New Hampshire,” The New Hampshire Archeologist, Vol. 45, No. 1, pages 1-29.

Kidder, Frederick, 1865/1909. “The Expeditions of Capt. John Lovewell and His Encounters with the Indians: Including a Particular Account of the Pequauket Battle, with a History of That Tribe; and a Reprint of Rev Thomas Symmes’s Sermon,” The Magazine of History, Extra Number – No. 5, published by William Abbatt, New York, page 26.

Lepper, Bradley T.. 2005. Ohio Archaeology: An Illustrated Chronicle of Ohio’s Ancient American Indian Culture. Orange Frazer Press, Wilmington, OH, pages 206-210.

Magli, Giulio. 2020. Archaeostronomy: Introduction to the Science of Stars and Stones, 2nd Edition. Springer, Switzerland, pages 27-28.

National Geodetic Toolkit, National Geodetic Survey website, revised 2018, INVERS3D interactive program.

Milner, George, 2021. The Mound Builders, Ancient Societies of Eastern North America, 2nd Edition, Thames and Hudson, New York, NY.

Neudorfer, Giovanna. 1980. Vermont’s Stone Chambers: An Inquiry into Their Past. Vermont Historical Society, Inc., pages 1 and 57.

Olsen, Brad. The Mysterious Stone Chambers of New England, Perceptive Travel website.

Parkman, Francis, 1898. Half Century of Conflict, France and England in North America, Vol 1. Little Brown and Company, Boston, page 261.

Penhallow, Samuel, 1726/1859. The History of the Wars of New England with the Eastern Indians. Reprinted from the Boston Edition of 1726, by J. Harpel Cincinnati, OH, pages 109-110.

Poor, Harry W. 1962. “Ossipee Ramblings Along Old Indian Trails.” Newsletter of the New Hampshire Archeological Society, vol 1: 9-14. Available at UNH Library.

Schultz, Eric B. and Tougias, Michael J., 1999. King Philip’s War, The History and Legacy of America’s Forgotten Conflict. The Countryman Press, Woodstock, VT, page 312.

Squier, Ephraim George and Davis, Edwin Hamilton, 1848/1973. Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley: Comprising the Results of Extensive Original Surveys and Explorations. AMS Press Inc, New York, NY.

Starbuck, David R.. 2006. The Archeology of New Hampshire. University of New Hampshire Press, Lebanon, NH, pages 106-108.

Sylvester, Herbert Milton, 1910. Indian Wars of New England, Vol. III. W.B. Clark, Co., Boston, MA.

Symmes, Thomas, V.D.M., 1725. Lowell Lamented, or a Sermon Occasion’d by the Fall Of the Brave Capt. John Lovewell and Several of his Valiant Company In the late Heroic Action at Piggwacket. B. Green Jun. for S. Gerrish, near the Brick Meeting House in Cornhill. Page iii.

Tatum, Jeremy. 2020. Physics: LibreTexts: Astronomy & Cosmology, Chapter 6.7: Precession.

Toner, Mike. 2008. “City Beneath the Mounds.” Archaeology, vol. 61, no. 6.

US Department of Agriculture. 1977. “Soil Survey of Carroll County.”

US Naval Observatory. 1998. Multiyear Interactive Computer Almanac 1800-2050. Willmann-Bell. CD ROM attached to book.

Williams, Gerald W. 2005. “References on the American Indian Use of Fire in Ecosystems.” USDA Forest Service.

Williamson, Ray A., 1984. Living the Sky, The Cosmos of the American Indian. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK, and London.

Writers of the Federal Writers’ Project of the WPA, for the State of NH, 1938. American Guide Series, New Hampshire, A Guide to the Granite State, Houghton Mifflin Co, Boston, Page 276.